How My Dad’s Immigrant Journey Shaped My View on Risk-Taking

My reflection on making asymmetric bets and playing the right game with decision-making

When I first stumbled upon this tweet, I instantly felt something click. As the son of immigrants, I grew up like many others, hearing about my parents’ journey to overcome adversity. My dad told me stories about how poor his family was and how he used education to pave a path to a better life in America. I have nothing but admiration and gratitude for both my parents.

At the same time, I struggled to translate their experience to the world I was growing up in. If theirs was a story of survival, mine wasn’t. I didn’t grow up with the same urgency around what might happen if I couldn’t make it. My parents impressed upon me the importance of hard work and education early on. And I enjoyed learning as a naturally curious kid. But I didn’t appreciate its importance the way my parents did. I thought a good education was a prerequisite to the “path”: I would study hard, get good grades, go to a great university, land an awesome job, make a lot of money, start a family, and live a great life.

This is all my parents could hope for me: what else is there?

I was looking for something else. It’s not that I didn’t want these things. But I wasn’t searching for them with the same hunger my parents had. While my parents’ experience was about survival and finding a better life, mine had to be different because it began on the premise of everything they achieved. Their life experience was centered around optimizing for stability, but mine couldn’t be. I realized if I did everything my parents wanted me to do, I would be navigating my life according to their experiences—and I would be playing the wrong game.

That’s when I started thinking more generally about risk and reward in my life—not just in terms of what could go wrong, but also in terms of what could go right.

My Decision Making Framework

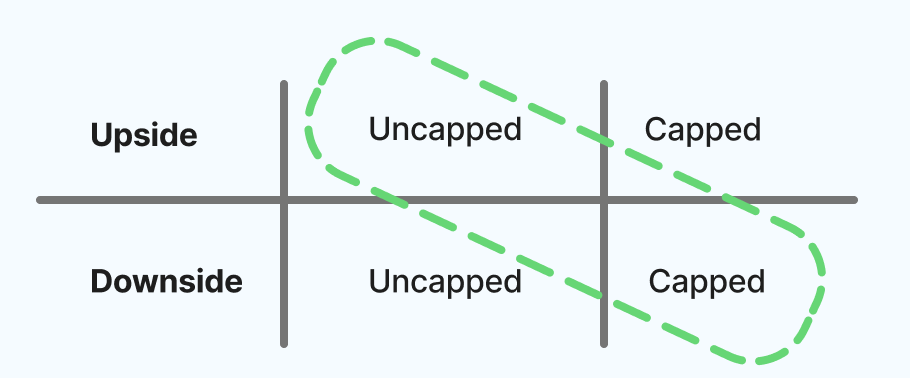

In a previous post, I wrote about getting comfortable with risk—the downside. But each decision also has potential reward—the upside. You can distill decision-making on these dimensions into a simple 2x2:

In this framework, uncapped means there is no predetermined limit to that outcome, whereas capped means it is fixed or constrained in some predictable ways.

The best decisions are high-leverage—offering outsized returns. By definition, these are asymmetric bets with uncapped upside, capped downside. The worst case is not bad, but the best case is potentially life changing even beyond what you originally imagined.

The other combinations are not so great:

Capped upside, uncapped downside: you take on a huge risk that can be disastrous, for an outcome that is simply not worth that risk. You have way more to lose than you have to gain. A good example is taking out a massive loan to purchase a home in a declining market. The home’s appreciation is limited by the market (capped upside) but if you lose your job or the housing market crashes, you can be financially ruined (uncapped downside). Try to avoid these bets.

Uncapped upside, uncapped downside: the huge risk has a potentially huge return. A good example is if a startup founder put their entire life savings on bootstrapping their business. If the startup succeeds, the outcome could be life-changing. If the startup fails, life-changing in a financially ruined way. Sometimes these bets may be worth it—if you feel you are controlling for the downside risk. Usually, we make these bets because we don’t see the downside as uncapped. We think we’ve mitigated the worst case.

Capped upside, capped downside: the risk is not great, but neither is the return. There is safety in predicting both the best case and worst case, and knowing the likelihood of each. A good example of this is investing in high-yield savings accounts. Your money will grow linearly (never exponentially) but even if the markets collapse, you’ll be protected. You never win big, but you never lose big either.

Finding the Right Moments for Asymmetry

When I looked at my life in the context of my parents’ decision-making, I realized I was getting stuck in a capped upside, capped downside mindset. This was not my parents’ fault.

They encouraged stability for me because they came from lives where they lacked financial stability. So they feared the worst case was that I ended up in a life similar to ones they escaped. All a parent wants is a better life for their child.

But I realized that my real downside was different than my parents’—largely because of their sacrifice and upbringing. They blessed me with a great education and every opportunity to better myself. I had a different floor. So my risk wasn’t instability, it was playing too small.

Over time, I’m learning to place more asymmetric bets. When I navigate decisions, I not only ask myself “what is the worst that can happen?” and “how likely is it?” — but I also think deeply about “what is the best possible thing that can happen?” and “how likely is that?”

I often go to my 2x2 framework before major decisions. It’s easy to misjudge both the upside and downside. But my bias is to focus on asymmetry, because it is the game I want to play.

I love my parents. They gave me a great life, and never once told me what to do with it. They gave me the freedom and autonomy to pursue what made me happy. They respected and trusted me to make mistakes and learn on my own.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to appreciate my dad’s journey with a new lens. His life story was hiding a powerful insight about asymmetric bets all along:

One well-timed asymmetric bet can change the course of your life forever. And when the upside is truly uncapped, it doesn’t just change your life—it compounds over time, creating opportunities you never could have predicted

His decision to take a job in America and leave everything behind in India was his asymmetric bet of a lifetime. He didn’t need a 2x2 to help him navigate it. But he knew when to take a bet that could change everything. He internalized the worst case, imagined the best case, and stepped into the unknown.

Because he made that bet, I get to make mine and I’m forever grateful.

The question is: when your moment comes, will you be ready to take yours?

Curious if you’d be willing to share, are there examples of asymmetric bets you’ve taken or are contemplating taking?